Music is a magical social glue. Whether you’re at a festival or in a church, there’s something about music that unites us in all our diversity – and believe it or not, there’s a neurobiological explanation.

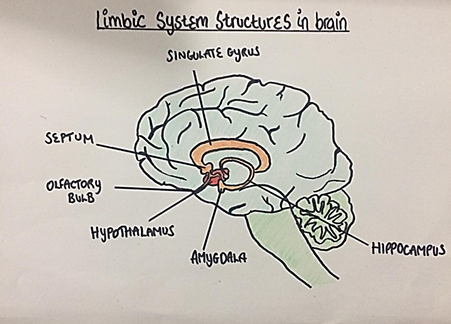

It seems as if our brains are hard-wired to experience music; from birth, humans show limbic responses to music. Steven Mithen, a professor of Archeolgy, claims the answer lies in our ancestral descent: his work argues a common decent between music and spoken language, claiming the two emerged from an emotional “proto-language” used by the Neanderthals. Yet the answer might lie elsewhere – an overwhelming number of studies have reported activity of the hippocampus during a musical experience.

The hippocampus is a notorious area of the brain, recognised for its role in memory, learning, spatial orientation and neurogenesis. However, numerous studies suggest it plays a crucial role in emotion, extending into the musical realm. Some researchers report hippocampal activity in response to music-evoked tenderness, peacefulness, frissons and sadness. Studies have even shown that synchronised rhythm with someone else increases activity of the hippocampus.

When activated by pleasurable music, the hippocampus interacts with the hypothalamus to lower levels of the hormone cortisol – in other words, it reduces emotional stress.

It’s telling that music activates this tender hotspot of emotion. Once activated, it evokes attachment-related emotions such as compassion, love and empathy – emotions which relate to the social functions of music. These feelings bind us in together during social functions, creating an authentic sense of community, closeness and connection.

Historically, music has also been a means of cultural identification, with individuals of different upbringing, ethnicity and lifestyles using it to express themselves.

Individual emotional states become one, promoting social cohesion mental well-being.

By nature, music involves social functions which are critical to our survival – without such homogeneity, we risk loneliness and social isolation, both risk factors for poor health and mortality.

We are social animals – the need for community is part of what makes us human.