How does music make you feel?

I’m not convinced that words can accurately describe it…

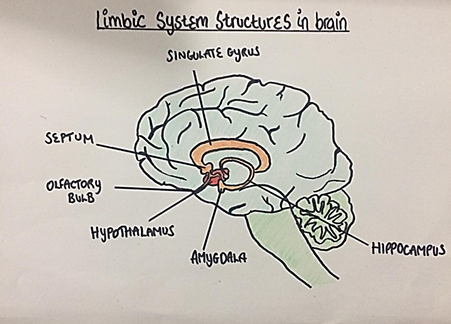

Think of that intense pleasure a moving piece evokes – for me, Frédéric Chopin’s Nocturne in C minor, Op. 48, No. 1 gives me that inexplicable emotion. You feel it as a chill, you see it as Goosebumps – its called musical frissons, and its extremely powerful. This response can be explained by activity of the dopaminergic mesolimbic reward pathway.

The Reward System

It all starts in the brain regions containing dopamine neurons: the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the Substantia nigra. When you experience something rewarding, such as food or drink, the neurotransmitter dopamine is released into target areas of the brain such as the Striatum and Prefrontal Cortex. Dopamine encodes information about reward expectation and motivates us to obtain pleasure. It typically acts as a reinforcer, meaning it makes us learn about rewards and seek them again in the future.

Structures in the striatum, called the nucleus accumbens and the caudate nucleus, are involved in representing hedonistic value. Yet strikingly, studies show that these regions and other components of the reward network are also active during music-evoked pleasure. This phylogenetically old network has enabled our survival, propelling us to obtain basic needs; that music activates this system suggests its role in persistence of the individual and species.

Musical Tension

Just as we find some music rewarding, other music can stir conflicting emotions. Like a good book, a musical piece is a coherent structure, composed of patterns and regularities. The building blocks of a structured piece are its acoustic elements: dynamics, tempo consonance or dissonance. As a piece becomes increasingly complex, so do the possibilities of what we expect to hear. So we are engaged throughout the piece, continuously predicting the next chord as our reward system awaits the verdict.

This musical tension grips your reward system – therefore you – with anticipation. It takes a skilled composer to build tension without causing unpleasantness. An example that comes to mind is Claude Debussy’s solo flute piece Syrinx: atonality is central to this haunting yet beautiful piece.

However, many pieces opt to build layers of tension, with the goal of resolution. If an unexpected chord occurs, emotion centers such as the amygdala and the orbito-frontal cortex are activated; once the structural breach is resolved, you feel relaxed. We naturally anticipate this relaxation, therefore our correct prediction causes an increase in dopamine. We are rewarded. Thus, it follows that unresolved music defies our prediction – in response, dopamine is not released, leaving us disappointed.

So, whether they knew it or not, Chopin and Debussy expertly gripped me by exploiting my dopaminergic mesolimbic reward pathway. The consequence? – a neurobiological and emotional journey every time I hear their music.